Weekly Shaarli

Week 25 (June 17, 2024)

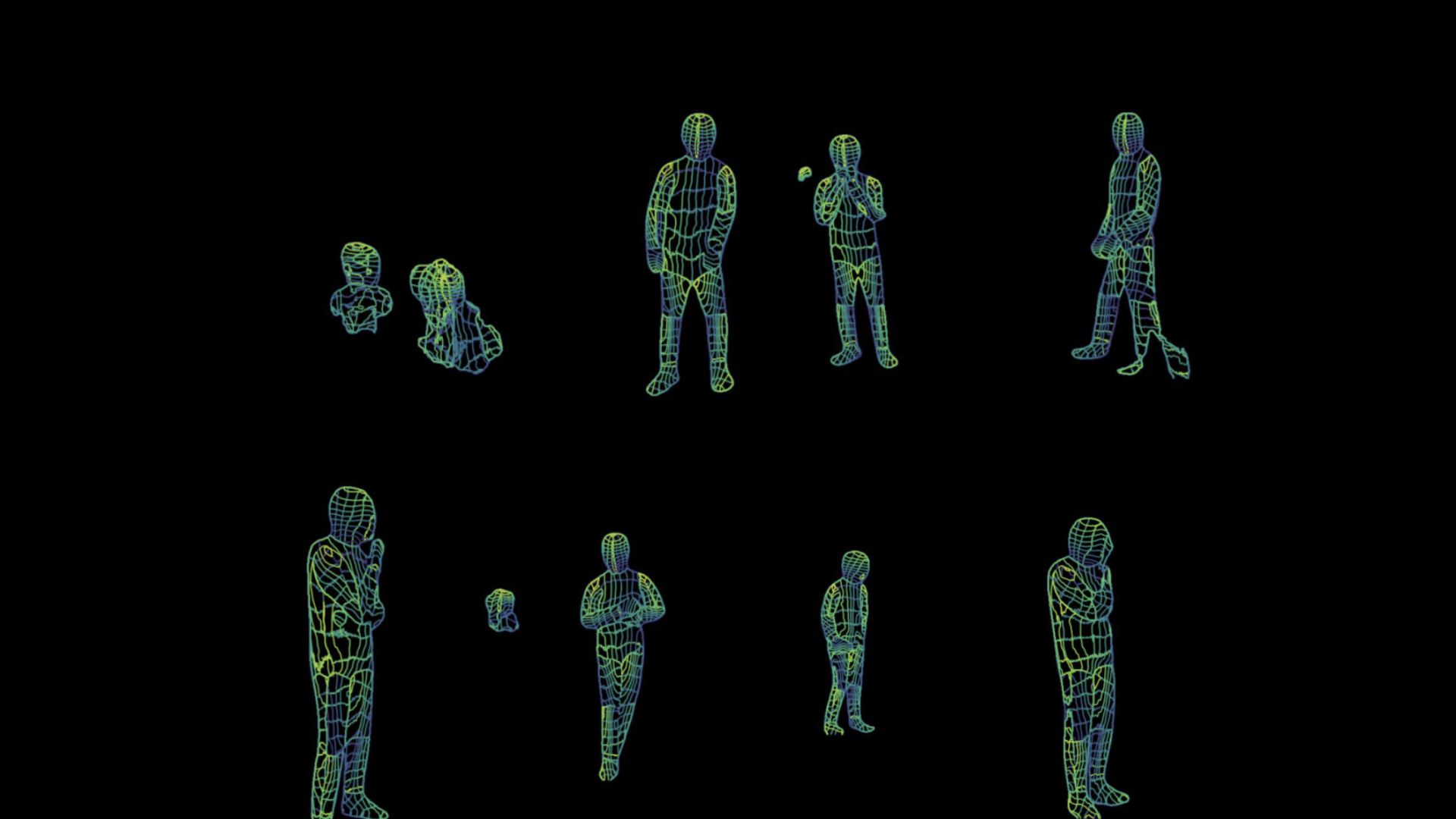

Scientists Are Getting Eerily Good at Using WiFi to 'See' People Through Walls in Detail

The signals from WiFi can be used to map a human body, according to a new paper.

January 17, 2023, 7:50pm

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University developed a method for detecting the three dimensional shape and movements of human bodies in a room, using only WiFi routers.

To do this, they used DensePose, a system for mapping all of the pixels on the surface of a human body in a photo. DensePose was developed by London-based researchers and Facebook’s AI researchers. From there, according to their recently-uploaded preprint paper published on arXiv, they developed a deep neural network that maps WiFi signals’ phase and amplitude sent and received by routers to coordinates on human bodies.

Researchers have been working on “seeing” people without using cameras or expensive LiDAR hardware for years. In 2013, a team of researchers at MIT found a way to use cell phone signals to see through walls; in 2018, another MIT team used WiFi to detect people in another room and translate their movements to walking stick-figures.

The Carnegie Mellon researchers wrote that they believe WiFi signals “can serve as a ubiquitous substitute” for normal RGB cameras, when it comes to “sensing” people in a room. Using WiFi, they wrote, overcomes obstacles like poor lighting and occlusion that regular camera lenses face.

Interestingly, they position this advancement as progress in privacy rights; “In addition, they protect individuals’ privacy and the required equipment can be bought at a reasonable price,” they wrote. “In fact, most households in developed countries already have WiFi at home, and this technology may be scaled to monitor the well-being of elder people or just identify suspicious behaviors at home.”

They don’t mention what “suspicious behaviors” might include, if this technology ever hits the mainstream market. But considering companies like Amazon are trying to put Ring camera drones inside our houses, it’s easy to imagine how widespread WiFi-enabled human-detection could be a force for good—or yet another exploitation of all of our privacy.

Why the Internet Isn’t Fun Anymore

The social-media Web as we knew it, a place where we consumed the posts of our fellow-humans and posted in return, appears to be over.

By Kyle Chayka October 9, 2023

Lately on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, my timeline is filled with vapid posts orbiting the same few topics like water whirlpooling down a drain. Last week, for instance, the chatter was dominated by talk of Taylor Swift’s romance with the football player Travis Kelce. If you tried to talk about anything else, the platform’s algorithmic feed seemed to sweep you into irrelevance. Users who pay for Elon Musk’s blue-check verification system now dominate the platform, often with far-right-wing commentary and outright disinformation; Musk rewards these users monetarily based on the engagement that their posts drive, regardless of their veracity. The decay of the system is apparent in the spread of fake news and mislabelled videos related to Hamas’s attack on Israel.

Elsewhere online, things are similarly bleak. Instagram’s feed pushes months-old posts and product ads instead of photos from friends. Google search is cluttered with junky results, and S.E.O. hackers have ruined the trick of adding “Reddit” to searches to find human-generated answers. Meanwhile, Facebook’s parent company, Meta, in its latest bid for relevance, is reportedly developing artificial-intelligence chatbots with various “sassy” personalities that will be added to its apps, including a role-playing D. & D. Dungeon Master based on Snoop Dogg. The prospect of interacting with such a character sounds about as appealing as texting with one of those spam bots that asks you if they have the right number.

The social-media Web as we knew it, a place where we consumed the posts of our fellow-humans and posted in return, appears to be over. The precipitous decline of X is the bellwether for a new era of the Internet that simply feels less fun than it used to be. Remember having fun online? It meant stumbling onto a Web site you’d never imagined existed, receiving a meme you hadn’t already seen regurgitated a dozen times, and maybe even playing a little video game in your browser. These experiences don’t seem as readily available now as they were a decade ago. In large part, this is because a handful of giant social networks have taken over the open space of the Internet, centralizing and homogenizing our experiences through their own opaque and shifting content-sorting systems. When those platforms decay, as Twitter has under Elon Musk, there is no other comparable platform in the ecosystem to replace them. A few alternative sites, including Bluesky and Discord, have sought to absorb disaffected Twitter users. But like sproutlings on the rain-forest floor, blocked by the canopy, online spaces that offer fresh experiences lack much room to grow.

One Twitter friend told me, of the platform’s current condition, “I’ve actually experienced quite a lot of grief over it.” It may seem strange to feel such wistfulness about a site that users habitually referred to as a “hellsite.” But I’ve heard the same from many others who once considered Twitter, for all its shortcomings, a vital social landscape. Some of them still tweet regularly, but their messages are less likely to surface in my Swift-heavy feed. Musk recently tweeted that the company’s algorithm “tries to optimize time spent on X” by, say, boosting reply chains and downplaying links that might send people away from the platform. The new paradigm benefits tech-industry “thread guys,” prompt posts in the “what’s your favorite Marvel movie” vein, and single-topic commentators like Derek Guy, who tweets endlessly about menswear. Algorithmic recommendations make already popular accounts and subjects even more so, shutting out the smaller, more magpie-ish voices that made the old version of Twitter such a lively destination. (Guy, meanwhile, has received so much algorithmic promotion under Musk that he accumulated more than half a million followers.)

The Internet today feels emptier, like an echoing hallway, even as it is filled with more content than ever. It also feels less casually informative. Twitter in its heyday was a source of real-time information, the first place to catch wind of developments that only later were reported in the press. Blog posts and TV news channels aggregated tweets to demonstrate prevailing cultural trends or debates. Today, they do the same with TikTok posts—see the many local-news reports of dangerous and possibly fake “TikTok trends”—but the TikTok feed actively dampens news and political content, in part because its parent company is beholden to the Chinese government’s censorship policies. Instead, the app pushes us to scroll through another dozen videos of cooking demonstrations or funny animals. In the guise of fostering social community and user-generated creativity, it impedes direct interaction and discovery.

According to Eleanor Stern, a TikTok video essayist with nearly a hundred thousand followers, part of the problem is that social media is more hierarchical than it used to be. “There’s this divide that wasn’t there before, between audiences and creators,” Stern said. The platforms that have the most traction with young users today—YouTube, TikTok, and Twitch—function like broadcast stations, with one creator posting a video for her millions of followers; what the followers have to say to one another doesn’t matter the way it did on the old Facebook or Twitter. Social media “used to be more of a place for conversation and reciprocity,” Stern said. Now conversation isn’t strictly necessary, only watching and listening.

Posting on social media might be a less casual act these days, as well, because we’ve seen the ramifications of blurring the border between physical and digital lives. Instagram ushered in the age of self-commodification online—it was the platform of the selfie—but TikTok and Twitch have turbocharged it. Selfies are no longer enough; video-based platforms showcase your body, your speech and mannerisms, and the room you’re in, perhaps even in real time. Everyone is forced to perform the role of an influencer. The barrier to entry is higher and the pressure to conform stronger. It’s no surprise, in this environment, that fewer people take the risk of posting and more settle into roles as passive consumers.

The patterns of life offscreen affect the makeup of the digital world, too. Having fun online was something that we used to do while idling in office jobs: stuck in front of computers all day, we had to find something on our screens to fill the down time. An earlier generation of blogs such as the Awl and Gawker seemed designed for aimless Internet surfing, delivering intermittent gossip, amusing videos, and personal essays curated by editors with quirky and individuated tastes. (When the Awl closed, in 2017, Jia Tolentino lamented the demise of “online freedom and fun.”) Now, in the aftermath of the pandemic, amid ongoing work-from-home policies, office workers are less tethered to their computers, and perhaps thus less inclined to chase likes on social media. They can walk away from their desks and take care of their children, walk their dog, or put their laundry in. This might have a salutary effect on individuals, but it means that fewer Internet-obsessed people are furiously creating posts for the rest of us to consume. The user growth rate of social platforms over all has slowed over the past several years; according to one estimate, it is down to 2.4 per cent in 2023.

That earlier generation of blogs once performed the task of aggregating news and stories from across the Internet. For a while, it seemed as though social-media feeds could fulfill that same function. Now it’s clear that the tech companies have little interest in directing users to material outside of their feeds. According to Axios, the top news and media sites have seen “organic referrals” from social media drop by more than half over the past three years. As of last week, X no longer displays the headlines for articles that users link to. The decline in referral traffic disrupts media business models, further degrading the quality of original content online. The proliferation of cheap, instant A.I.-generated content promises to make the problem worse.

Choire Sicha, the co-founder of the Awl and now an editor at New York, told me that he traces the seeds of social media’s degradation back a decade. “If I had a time machine I’d go back and assassinate 2014,” he said. That was the year of viral phenomena such as Gamergate, when a digital mob of disaffected video-game fans targeted journalists and game developers on social media; Ellen DeGeneres’s selfie with a gaggle of celebrities at the Oscars, which got retweeted millions of times; and the brief, wondrous fame of Alex, a random teen retail worker from Texas who won attention for his boy-next-door appearance. In those events, we can see some of the nascent forces that would solidify in subsequent years: the tyranny of the loudest voices; the entrenchment of traditional fame on new platforms; the looming emptiness of the content that gets most furiously shared and promoted. But at that point they still seemed like exceptions rather than the rule.

I have been trying to recall the times I’ve had fun online unencumbered by anonymous trolling, automated recommendations, or runaway monetization schemes. It was a long time ago, before social networks became the dominant highways of the Internet. What comes to mind is a Web site called Orisinal that hosted games made with Flash, the late interactive animation software that formed a significant part of the kitschy Internet of the two-thousands, before everyone began posting into the same platform content holes. The games on the site were cartoonish, cute, and pastel-colored, involving activities like controlling a rabbit jumping on stars into the sky or helping mice make a cup of tea. Orisinal was there for anyone to stumble upon, without the distraction of follower counts or sponsored content. You could e-mail the site to a friend, but otherwise there was nothing to share. That old version of the Internet is still there, but it’s been eclipsed by the modes of engagement that the social networks have incentivized. Through Reddit, I recently dug up an emulator of all the Orisinal games and quickly got absorbed into one involving assisting deer leaping across a woodland gap. My only reward was a personal high score. But it was more satisfying, and less lonely, than the experience these days on X. ♦

Underage Workers Are Training AI

Companies that provide Big Tech with AI data-labeling services are inadvertently hiring young teens to work on their platforms, often exposing them to traumatic content.

Like most kids his age, 15-year-old Hassan spent a lot of time online. Before the pandemic, he liked playing football with local kids in his hometown of Burewala in the Punjab region of Pakistan. But Covid lockdowns made him something of a recluse, attached to his mobile phone. “I just got out of my room when I had to eat something,” says Hassan, now 18, who asked to be identified under a pseudonym because he was afraid of legal action. But unlike most teenagers, he wasn’t scrolling TikTok or gaming. From his childhood bedroom, the high schooler was working in the global artificial intelligence supply chain, uploading and labeling data to train algorithms for some of the world’s largest AI companies.

The raw data used to train machine-learning algorithms is first labeled by humans, and human verification is also needed to evaluate their accuracy. This data-labeling ranges from the simple—identifying images of street lamps, say, or comparing similar ecommerce products—to the deeply complex, such as content moderation, where workers classify harmful content within data scraped from all corners of the internet. These tasks are often outsourced to gig workers, via online crowdsourcing platforms such as Toloka, which was where Hassan started his career.

A friend put him on to the site, which promised work anytime, from anywhere. He found that an hour’s labor would earn him around $1 to $2, he says, more than the national minimum wage, which was about $0.26 at the time. His mother is a homemaker, and his dad is a mechanical laborer. “You can say I belong to a poor family,” he says. When the pandemic hit, he needed work more than ever. Confined to his home, online and restless, he did some digging, and found that Toloka was just the tip of the iceberg.

“AI is presented as a magical box that can do everything,” says Saiph Savage, director of Northeastern University’s Civic AI Lab. “People just simply don’t know that there are human workers behind the scenes.”

At least some of those human workers are children. Platforms require that workers be over 18, but Hassan simply entered a relative’s details and used a corresponding payment method to bypass the checks—and he wasn’t alone in doing so. WIRED spoke to three other workers in Pakistan and Kenya who said they had also joined platforms as minors, and found evidence that the practice is widespread.

“When I was still in secondary school, so many teens discussed online jobs and how they joined using their parents' ID,” says one worker who joined Appen at 16 in Kenya, who asked to remain anonymous. After school, he and his friends would log on to complete annotation tasks late into the night, often for eight hours or more.

Appen declined to give an attributable comment.

“If we suspect a user has violated the User Agreement, Toloka will perform an identity check and request a photo ID and a photo of the user holding the ID,” Geo Dzhikaev, head of Toloka operations, says.

Driven by a global rush into AI, the global data labeling and collection industry is expected to grow to over $17.1 billion by 2030, according to Grand View Research, a market research and consulting company. Crowdsourcing platforms such as Toloka, Appen, Clickworker, Teemwork.AI, and OneForma connect millions of remote gig workers in the global south to tech companies located in Silicon Valley. Platforms post micro-tasks from their tech clients, which have included Amazon, Microsoft Azure, Salesforce, Google, Nvidia, Boeing, and Adobe. Many platforms also partner with Microsoft’s own data services platform, the Universal Human Relevance System (UHRS).

These workers are predominantly based in East Africa, Venezuela, Pakistan, India, and the Philippines—though there are even workers in refugee camps, who label, evaluate, and generate data. Workers are paid per task, with remuneration ranging from a cent to a few dollars—although the upper end is considered something of a rare gem, workers say. “The nature of the work often feels like digital servitude—but it's a necessity for earning a livelihood,” says Hassan, who also now works for Clickworker and Appen.

Sometimes, workers are asked to upload audio, images, and videos, which contribute to the data sets used to train AI. Workers typically don’t know exactly how their submissions will be processed, but these can be pretty personal: On Clickworker’s worker jobs tab, one task states: “Show us you baby/child! Help to teach AI by taking 5 photos of your baby/child!” for €2 ($2.15). The next says: “Let your minor (aged 13-17) take part in an interesting selfie project!”

Some tasks involve content moderation—helping AI distinguish between innocent content and that which contains violence, hate speech, or adult imagery. Hassan shared screen recordings of tasks available the day he spoke with WIRED. One UHRS task asked him to identify “fuck,” “c**t,” “dick,” and “bitch” from a body of text. For Toloka, he was shown pages upon pages of partially naked bodies, including sexualized images, lingerie ads, an exposed sculpture, and even a nude body from a Renaissance-style painting. The task? Decipher the adult from the benign, to help the algorithm distinguish between salacious and permissible torsos.

Hassan recalls moderating content while under 18 on UHRS that, he says, continues to weigh on his mental health. He says the content was explicit: accounts of rape incidents, lifted from articles quoting court records; hate speech from social media posts; descriptions of murders from articles; sexualized images of minors; naked images of adult women; adult videos of women and girls from YouTube and TikTok.

Many of the remote workers in Pakistan are underage, Hassan says. He conducted a survey of 96 respondents on a Telegram group chat with almost 10,000 UHRS workers, on behalf of WIRED. About a fifth said they were under 18.

Awais, 20, from Lahore, who spoke on condition that his first name not be published, began working for UHRS via Clickworker at 16, after he promised his girlfriend a birthday trip to the turquoise lakes and snow-capped mountains of Pakistan’s northern region. His parents couldn’t help him with the money, so he turned to data work, joining using a friend’s ID card. “It was easy,” he says.

He worked on the site daily, primarily completing Microsoft’s “Generic Scenario Testing Extension” task. This involved testing homepage and search engine accuracy. In other words, did selecting “car deals” on the MSN homepage bring up photos of cars? Did searching “cat” on Bing show feline images? He was earning $1 to $3 each day, but he found the work both monotonous and infuriating. At times he found himself working 10 hours for $1, because he had to do unpaid training to access certain tasks. Even when he passed the training, there might be no task to complete; or if he breached the time limit, they would suspend his account, he says. Then seemingly out of nowhere, he got banned from performing his most lucrative task—something workers say happens regularly. Bans can occur for a host of reasons, such as giving incorrect answers, answering too fast, or giving answers that deviate from the average pattern of other workers. He’d earned $70 in total. It was almost enough to take his high school sweetheart on the trip, so Awais logged off for good.

Clickworker did not respond to requests for comment. Microsoft declined to comment.

“In some instances, once a user finishes the training, the quota of responses has already been met for that project and the task is no longer available,” Dzhikaev said. “However, should other similar tasks become available, they will be able to participate without further training.”

Researchers say they’ve found evidence of underage workers in the AI industry elsewhere in the world. Julian Posada, assistant professor of American Studies at Yale University, who studies human labor and data production in the AI industry, says that he’s met workers in Venezuela who joined platforms as minors.

Bypassing age checks can be pretty simple. The most lenient platforms, like Clickworker and Toloka, simply ask workers to state they are over 18; the most secure, such as Remotasks, employ face recognition technology to match workers to their photo ID. But even that is fallible, says Posada, citing one worker who says he simply held the phone to his grandmother’s face to pass the checks. The sharing of a single account within family units is another way minors access the work, says Posada. He found that in some Venezuelan homes, when parents cook or run errands, children log on to complete tasks. He says that one family of six he met, with children as young as 13, all claimed to share one account. They ran their home like a factory, Posada says, so that two family members were at the computers working on data labeling at any given point. “Their backs would hurt because they have been sitting for so long. So they would take a break, and then the kids would fill in,” he says.

The physical distances between the workers training AI and the tech giants at the other end of the supply chain—“the deterritorialization of the internet,” Posada calls it—creates a situation where whole workforces are essentially invisible, governed by a different set of rules, or by none.

The lack of worker oversight can even prevent clients from knowing if workers are keeping their income. One Clickworker user in India, who requested anonymity to avoid being banned from the site, told WIRED he “employs” 17 UHRS workers in one office, providing them with a computer, mobile, and internet, in exchange for half their income. While his workers are aged between 18 and 20, due to Clickworker’s lack of age certification requirements, he knows of teenagers using the platform.

In the more shadowy corners of the crowdsourcing industry, the use of child workers is overt.

Captcha (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) solving services, where crowdsourcing platforms pay humans to solve captchas, are a less understood part in the AI ecosystem. Captchas are designed to distinguish a bot from a human—the most notable example being Google’s reCaptcha, which asks users to identify objects in images to enter a website. The exact purpose of services that pay people to solve them remains a mystery to academics, says Posada. “But what I can confirm is that many companies, including Google's reCaptcha, use these services to train AI models,” he says. “Thus, these workers indirectly contribute to AI advancements.”

Google did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

There are at least 152 active services, mostly based in China, with more than half a million people working in the underground reCaptcha market, according to a 2019 study by researchers from Zhejiang University in Hangzhou.

“Stable job for everyone. Everywhere,” one service, Kolotibablo, states on its website. The company has a promotional website dedicated to showcasing its worker testimonials, which includes images of young children from across the world. In one, a smiling Indonesian boy shows his 11th birthday cake to the camera. “I am very happy to be able to increase my savings for the future,” writes another, no older than 7 or 8. A 14-year-old girl in a long Hello Kitty dress shares a photo of her workstation: a laptop on a pink, Barbie-themed desk.

Not every worker WIRED interviewed felt frustrated with the platforms. At 17, most of Younis Hamdeen’s friends were waiting tables. But the Pakistani teen opted to join UHRS via Appen instead, using the platform for three or four hours a day, alongside high school, earning up to $100 a month. Comparing products listed on Amazon was the most profitable task he encountered. “I love working for this platform,” Hamdeen, now 18, says, because he is paid in US dollars—which is rare in Pakistan—and so benefits from favorable exchange rates.

But the fact that the pay for this work is incredibly low compared to the wages of in-house employees of the tech companies, and that the benefits of the work flow one way—from the global south to the global north, leads to uncomfortable parallels. “We do have to consider the type of colonialism that is being promoted with this type of work,” says the Civic AI Lab’s Savage.

Hassan recently got accepted to a bachelor’s program in medical lab technology. The apps remain his sole income, working an 8 am to 6 pm shift, followed by 2 am to 6 am. However, his earnings have fallen to just $100 per month, as demand for tasks has outstripped supply, as more workers have joined since the pandemic.

He laments that UHRS tasks can pay as little as 1 cent. Even on higher-paid jobs, such as occasional social media tasks on Appen, the amount of time he needs to spend doing unpaid research means he needs to work five or six hours to complete an hour of real-time work, all to earn $2, he says.

“It’s digital slavery,” says Hassan.

Pop Culture Has Become an Oligopoly

A cartel of superstars has conquered culture. How did it happen, and what should we do about it?

Adam Mastroianni May 02, 2022

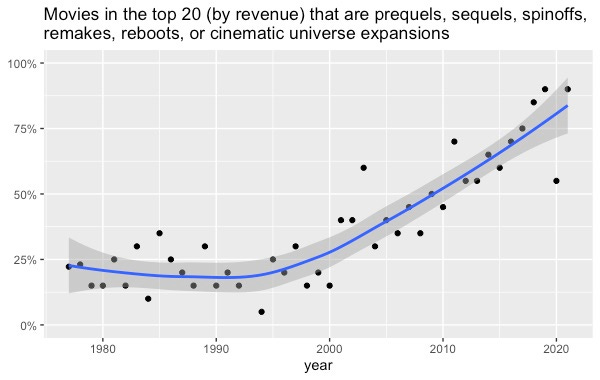

You may have noticed that every popular movie these days is a remake, reboot, sequel, spinoff, or cinematic universe expansion. In 2021, only one of the ten top-grossing films––the Ryan Reynolds vehicle Free Guy––was an original. There were only two originals in 2020’s top 10, and none at all in 2019.

People blame this trend on greedy movie studios or dumb moviegoers or competition from Netflix or humanity running out of ideas. Some say it’s a sign of the end of movies. Others claim there’s nothing new about this at all.

Some of these explanations are flat-out wrong; others may contain a nugget of truth. But all of them are incomplete, because this isn’t just happening in movies. In every corner of pop culture––movies, TV, music, books, and video games––a smaller and smaller cartel of superstars is claiming a larger and larger share of the market. What used to be winners-take-some has grown into winners-take-most and is now verging on winners-take-all. The (very silly) word for this oligopoly, like a monopoly but with a few players instead of just one.

I’m inherently skeptical of big claims about historical shifts. I recently published a paper showing that people overestimate how much public opinion has changed over the past 50 years, so naturally I’m on the lookout for similar biases here. But this shift is not an illusion. It’s big, it’s been going on for decades, and it’s happening everywhere you look. So let’s get to the bottom of it.

(Data and code available here.)

Movies

At the top of the box office charts, original films have gone extinct.

I looked at the 20 top-grossing movies going all the way back to 1977 (source), and I coded whether each was part of what film scholars call a “multiplicity”—sequels, prequels, franchises, spin-offs, cinematic universe expansions, etc. This required some judgment calls. Lots of movies are based on books and TV shows, but I only counted them as multiplicities if they were related to a previous movie. So 1990’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles doesn’t get coded as a multiplicity, but 1991’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze does, and so does the 2014 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles remake. I also probably missed a few multiplicities, especially in earlier decades, since sometimes it’s not obvious that a movie has some connection to an earlier movie.

Regardless, the shift is gigantic. Until the year 2000, about 25% of top-grossing movies were prequels, sequels, spinoffs, remakes, reboots, or cinematic universe expansions. Since 2010, it’s been over 50% ever year. In recent years, it’s been close to 100%.

Original movies just aren’t popular anymore, if they even get made in the first place.

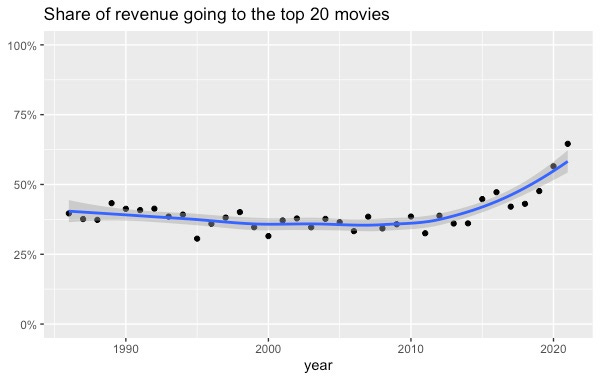

Top movies have also recently started taking a larger chunk of the market. I extracted the revenue of the top 20 movies and divided it by the total revenue of the top 200 movies, going all the way back to 1986 (source). The top 20 movies captured about 40% of all revenue until 2015, when they started gobbling up even more.

Television

Thanks to cable and streaming, there's way more stuff on TV today than there was 50 years ago. So it would make sense if a few shows ruled the early decades of TV, and now new shows constantly displace each other at the top of the viewership charts.

Instead, the opposite has happened. I pulled the top 30 most-viewed TV shows from 1950 to 2019 (source) and found that fewer and fewer franchises rule a larger and larger share of the airwaves. In fact, since 2000, about a third of the top 30 most-viewed shows are either spinoffs of other shows in the top 30 (e.g., CSI and CSI: Miami) or multiple broadcasts of the same show (e.g., American Idol on Monday and American Idol on Wednesday).

Two caveats to this data. First, I’m probably slightly undercounting multiplicities from earlier decades, where the connections between shows might be harder for a modern viewer like me to understand––maybe one guy hosted multiple different shows, for example. And second, the Nielsen ratings I’m using only recently started accurately measuring viewership on streaming platforms. But even in 2019, only 14% of viewing time was spent on streaming, so this data isn’t missing much.

Music

It used to be that a few hitmakers ruled the charts––The Beatles, The Eagles, Michael Jackson––while today it’s a free-for-all, right?

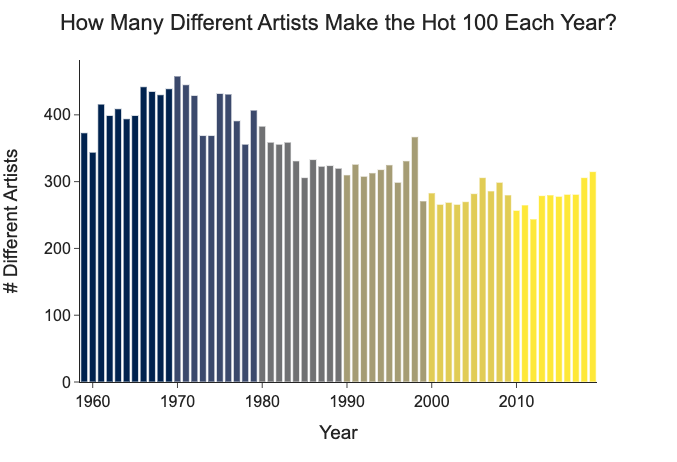

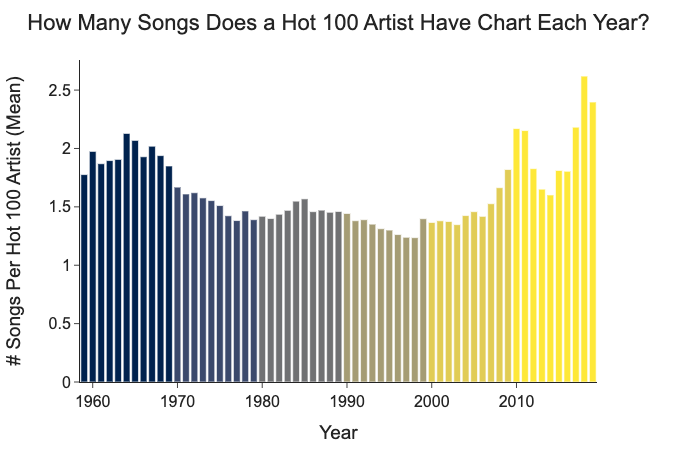

Nope. A data scientist named Azhad Syed has done the analysis, and he finds that the number of artists on the Billboard Hot 100 has been decreasing for decades.

Chart by Azhad Syed

And since 2000, the number of hits per artist on the Hot 100 has been increasing.

Chart by Azhad Syed

(Azhad says he’s looking for a job––you should hire him!)

A smaller group of artists tops the charts, and they produce more of the chart-toppers. Music, too, has become an oligopoly.

Books

Literature feels like a different world than movies, TV, and music, and yet the trend is the same.

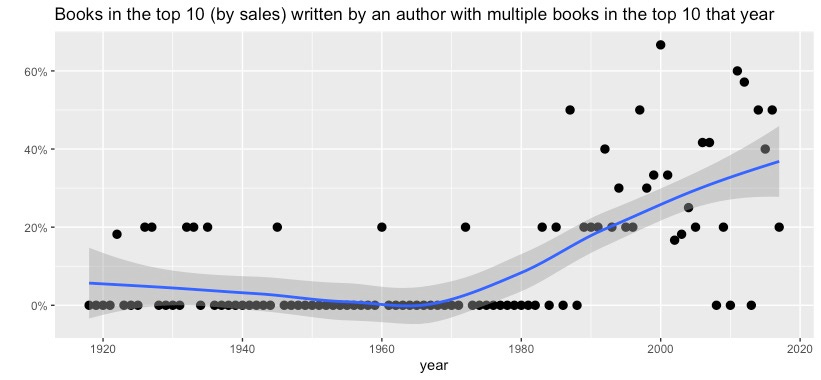

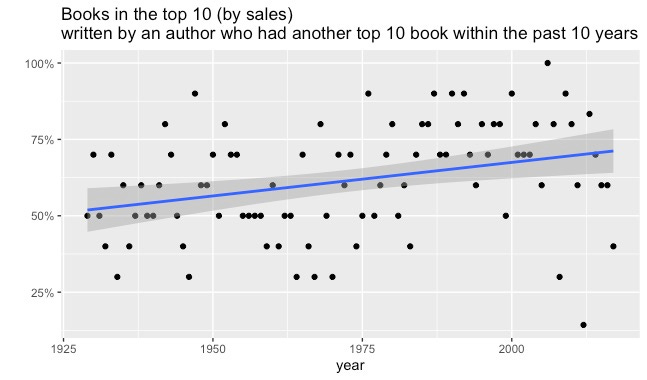

Using LiteraryHub's list of the top 10 bestselling books for every year from 1919 to 2017, I found that the oligopoly has come to book publishing as well. There are a couple ways we can look at this. First, we can look at the percentage of repeat authors in the top 10––that is, the number of books in the top 10 that were written by an author with another book in the top 10.

It used to be pretty rare for one author to have multiple books in the top 10 in the same year. Since 1990, it’s happened almost every year. No author ever had three top 10 books in one year until Danielle Steel did it 1998. In 2011, John Grisham, Kathryn Stockett, and Stieg Larsson all had two chart-topping books each.

We can also look at the percentage of authors in the top 10 were already famous––say, they had a top 10 book within the past 10 years. That has increased over time, too.

In the 1950s, a little over half of the authors in the top 10 had been there before. These days, it’s closer to 75%.

Video games

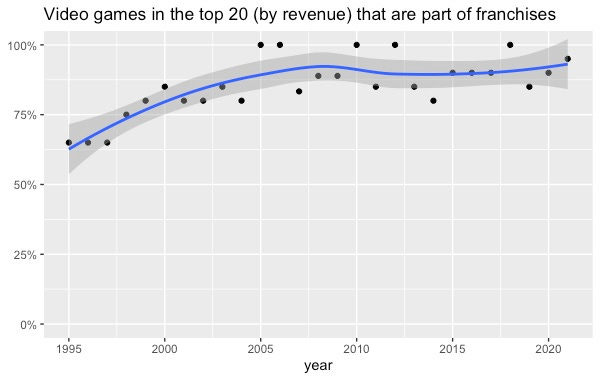

I tracked down the top 20 bestselling video games for each year from 1995 to 2021 (sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) and coded whether each belongs to a preexisting video game franchise. (Some games, like Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, belong to franchises outside of video games. For these, I coded the first installment as originals and any subsequent installments as franchise games.)

The oligopoly rules video games too:

In the late 1990s, 75% or less of bestselling video games were franchise installments. Since 2005, it’s been above 75% every year, and sometimes it’s 100%. At the top of the charts, it’s all Mario, Zelda, Call of Duty, and Grand Theft Auto.

Why is this happening?

Any explanation for the rise of the pop oligopoly has to answer two questions: why have producers started producing more of the same thing, and why are consumers consuming it? I think the answers to the first question are invasion, consolidation, and innovation. I think the answer to the second question is proliferation.

Invasion

Software and the internet have made it easier than ever to create and publish content. Most of the stuff that random amateurs make is crap and nobody looks at it, but a tiny proportion gets really successful. This might make media giants choose to produce and promote stuff that independent weirdos never could, like an Avengers movie. This can’t explain why oligopolization started decades ago––YouTube only launched in 2005, for example, and most Americans didn’t have broadband until 2007––but it might explain why it’s accelerated and stuck around.

Consolidation

Big things like to eat, defeat, and outcompete smaller things. So over time, big things should get bigger and small things should die off. Indeed, movie studios, music labels, TV stations, and publishers of books and video games have all consolidated. Maybe it’s inevitable that major producers of culture will suck up or destroy everybody else, leaving nothing but superstars and blockbusters. Indeed, maybe cultural oligopoly is merely a transition state before we reach cultural monopoly.

Innovation

You may think there’s nothing left to discover in art forms as old as literature and music, and that they simply iterate as fashions change. But it took humans [thousands of years](http://www.essentialvermeer.com/technique/perspective/history.html#:~:text=In its mathematical form%2C linear,De pictura [On Painting]) to figure out how to create the illusion of depth in paintings. Novelists used to think that sentences had to be long and complicated until Hemingway came along, wrote some snappy prose, and changed everything. Even very old art forms, then, may have secrets left to discover. Maybe the biggest players in culture discovered some innovations that won them a permanent, first-mover chunk of market share. I can think of a few:

- In books: lightning-quick plots and chapter-ending cliffhangers. Nobody thinks The Da Vinci Code is high literature, but it’s a book that really really wants you to read it. And a lot of people did!

- In music: sampling. Musicians [seem to sample more often these days](https://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2019/03/2019-the-state-of-sampling-draft.html#:~:text=1 in 5 Songs on,usually between 20-25%). Now we not only remake songs; we franchise them too.

- In movies, TV, and video games: cinematic universes. Studios have finally figured out that once audiences fall in love with fictional worlds, they want to spend lots of time in them. Marvel, DC, and Star Wars are the most famous, but there are also smaller universe expansions like Better Call Saul and El Camino from Breaking Bad and The Many Saints of Newark from The Sopranos. Video game developers have understood this for even longer, which is why Mario does everything from playing tennis to driving go-karts to, you know, being a piece of paper.

Proliferation

Invasion, consolidation, and innovation can, I think, explain the pop oligopoly from the supply side. But all three require a willing audience. So why might people be more open to experiencing the same thing over and over again?

As options multiply, choosing gets harder. You can’t possibly evaluate everything, so you start relying on cues like “this movie has Tom Hanks in it” or “I liked Red Dead Redemption, so I’ll probably like Red Dead Redemption II,” which makes you less and less likely to pick something unfamiliar.

Another way to think about it: more opportunities means higher opportunity costs, which could lead to lower risk tolerance. When the only way to watch a movie is to go pick one of the seven playing at your local AMC, you might take a chance on something new. But when you’ve got a million movies to pick from, picking a safe, familiar option seems more sensible than gambling on an original.

This could be happening across all of culture at once. Movies don’t just compete with other movies. They compete with every other way of spending your time, and those ways are both infinite and increasing. There are now [60,000](https://www.gutenberg.org/#:~:text=Project Gutenberg is a library of over 60%2C000 free eBooks) free books on Project Gutenberg, Spotify [says](https://newsroom.spotify.com/company-info/#:~:text=Discover%2C manage and share over,ad-free music listening experience) it has 78 million songs and 4 million podcast episodes, and humanity uploads 500 hours of video to YouTube [every minute](https://www.statista.com/statistics/259477/hours-of-video-uploaded-to-youtube-every-minute/#:~:text=As of February 2020%2C more,for online video has grown). So uh, yeah, the Tom Hanks movie sounds good.

What do we do about it?

Some may think that the rise of the pop oligopoly means the decline of quality. But the oligopoly can still make art: Red Dead Redemption II is a terrific game, “Blinding Lights” is a great song, and Toy Story 4 is a pretty good movie. And when you look back at popular stuff from a generation ago, there was plenty of dreck. We’ve forgotten the pulpy Westerns and insipid romances that made the bestseller lists while books like The Great Gatsby, Brave New World, and Animal Farm did not. American Idol is not so different from the televised talent shows of the 1950s. Popular culture has always been a mix of the brilliant and the banal, and nothing I’ve shown you suggests that the ratio has changed.

The problem isn’t that the mean has decreased. It’s that the variance has shrunk. Movies, TV, music, books, and video games should expand our consciousness, jumpstart our imaginations, and introduce us to new worlds and stories and feelings. They should alienate us sometimes, or make us mad, or make us think. But they can’t do any of that if they only feed us sequels and spinoffs. It’s like eating macaroni and cheese every single night forever: it may be comfortable, but eventually you’re going to get scurvy.

We haven’t fully reckoned with what the cultural oligopoly might be doing to us. How much does it stunt our imaginations to play the same video games we were playing 30 years ago? What message does it send that one of the most popular songs in the 2010s was about how a 1970s rock star was really cool? How much does it dull our ambitions to watch 2021’s The Matrix: Resurrections, where the most interesting scene is just Neo watching the original Matrix from 1999? How inspiring is it to watch tiny variations on the same police procedurals and reality shows year after year? My parents grew up with the first Star Wars movie, which had the audacity to create an entire universe. My niece and nephews are growing up with the ninth Star Wars movie, which aspires to move merchandise. Subsisting entirely on cultural comfort food cannot make us thoughtful, creative, or courageous.

Fortunately, there’s a cure for our cultural anemia. While the top of the charts has been oligopolized, the bottom remains a vibrant anarchy. There are weird books and funky movies and bangers from across the sea. Two of the most interesting video games of the past decade put you in the role of an immigration officer and an insurance claims adjuster. Every strange thing, wonderful and terrible, is available to you, but they’ll die out if you don’t nourish them with your attention. Finding them takes some foraging and digging, and then you’ll have to stomach some very odd, unfamiliar flavors. That’s good. Learning to like unfamiliar things is one of the noblest human pursuits; it builds our empathy for unfamiliar people. And it kindles that delicate, precious fire inside us––without it, we might as well be algorithms. Humankind does not live on bread alone, nor can our spirits long survive on a diet of reruns.

Réseaux sociaux : la fabrique de l’hostilité politique ?

Publié: 17 juin 2024, 15:21 CEST

Depuis quelques années, les réseaux sociaux comme Facebook et X (anciennement Twitter) sont devenus la cible d’accusations nombreuses : facteurs de diffusion de « fake news » à grande échelle, instruments de déstabilisation des démocraties par la Russie et la Chine, machines à capturer notre attention pour la vendre à des marchands de toutes sortes, théâtres d’un ciblage publicitaire toujours plus personnalisé et manipulateur, etc. En atteste le succès de documentaires et d’essais sur le coût humain, jugé considérable, des réseaux sociaux, comme The Social Dilemma sur Netflix.

L’un de ces discours, en particulier, rend les plates-formes digitales et leurs algorithmes responsables de l’amplification de l’hostilité en ligne et de la polarisation politique dans la société. Avec les discussions en ligne anonymes, affirment certains, n’importe qui serait susceptible de devenir un troll, c’est-à-dire une personne agressive, cynique et dépourvue de compassion, ou de se « radicaliser ».

Des travaux récents en sciences sociales quantitatives et en psychologie scientifique permettent toutefois d’apporter quelques correctifs à ce récit, excessivement pessimiste.

L’importance du contexte sociopolitique et de la psychologie

Pour commencer, plusieurs études suggèrent que si les individus font régulièrement l’expérience de discussions sur des sujets politiques qui deviennent conflictuelles, cette incivilité est en partie liée à des facteurs psychologiques et socio-économiques qui préexistent aux plates-formes digitales.

Dans une étude interculturelle de grande envergure, nous avons interrogé plus de 15 000 personnes via des panels représentatifs dans trente nations très diverses (France, Irak, Thaïlande, Pakistan, etc.) sur leurs expériences des conversations sur Internet. Notre première découverte est que ce sont dans les pays les plus inégalitaires économiquement et les moins démocratiques que les individus sont le plus souvent l’objet d’invectives hostiles de la part de leurs concitoyens sur les réseaux (comme en Turquie ou au Brésil). Ce phénomène découle manifestement des frustrations générées par ces sociétés plus répressives des aspirations individuelles.

Notre étude montre en outre que les individus qui s’adonnent le plus à l’hostilité en ligne sont aussi ceux qui sont les plus disposés à la recherche de statut social par la prise de risque. Ce trait de personnalité correspond à une orientation vers la dominance, c’est-à-dire à chercher à soumettre les autres à sa volonté (y compris par l’intimidation). Dans nos données interculturelles, nous observons que les individus ayant ce type de traits dominants sont nombreux dans les pays inégalitaires et non démocratiques. Des analyses indépendantes montrent d’ailleurs que la dominance est un élément clé de la psychologie de la conflictualité politique, puisqu’elle prédit également davantage de partage de ‘fake news’ moquant ou insultant les opposants politiques sur Internet, et plus d’attrait pour le conflit politique hors ligne, notamment.

Répliquant une étude antérieure, nous trouvons par ailleurs que ces individus motivés par la recherche de statut par la prise de risque, qui admettent le plus se comporter de manière hostile sur Internet, sont aussi ceux qui sont plus susceptibles d’interagir de manière agressive ou toxique dans des discussions en face à face (la corrélation entre l’hostilité en ligne et hors ligne est forte, de l’ordre de β = 0,77).

En résumé, l’hostilité politique en ligne semble largement être le fruit de personnalités particulières, rendues agressives par les frustrations engendrées par des contextes sociaux inégalitaires, et activant notre tendance à voir le monde en termes de “nous” vs « eux ». Au plan politique, réduire les disparités de richesses entre groupes et rendre nos institutions plus démocratiques constituent des objectifs probablement incontournables si nous souhaitons faire advenir un Internet (et une société civile) plus harmonieux.

Les réseaux : prismes exagérant l’hostilité ambiante

Si notre étude replace l’hostilité politique en ligne dans un plus large contexte, elle ne nie pas tout rôle aux plates-formes dans la production de la polarisation politique pour autant.

Les réseaux sociaux permettent à un contenu d’être diffusé à l’identique à des millions de personnes (à l’inverse de la communication verbale, lieu de distorsions inévitables). À ce titre, ils peuvent mésinformer ou mettre en colère des millions de personnes à un très faible coût. Ceci est vrai que l’information fausse ou toxique soit créée intentionnellement pour générer des clics, ou qu’elle soit le fruit involontaire des biais politiques d’un groupe politique donné.

[Déjà plus de 120 000 abonnements aux newsletters The Conversation. Et vous ? Abonnez-vous aujourd’hui pour mieux comprendre les grands enjeux du monde.]

Si les échanges sur les réseaux sociaux manquent souvent de civilité, c’est également à cause de la possibilité qu’ils offrent d’échanger avec des étrangers anonymes, dépersonnalisés. Cette expérience unique à l’ère Internet réduit le sentiment de responsabilité personnelle, ainsi que l’empathie vis-à-vis d’interlocuteurs que nous ne voyons plus comme des personnes mais comme les membres interchangeables de « tribus » politiques.

Des analyses récentes rappellent par ailleurs que les réseaux sociaux – comme le journalisme, à bien des égards – opèrent moins comme le miroir que comme le prisme déformant de la diversité des opinions dans la société.

Les posts politiques indignés et potentiellement insultants sont souvent le fait de personnes plus déterminées à s’exprimer et radicales que la moyenne – que ce soit pour signaler leurs engagements, exprimer une colère, faire du prosélytisme, etc. Même lorsqu’ils représentent une assez faible proportion de la production écrite sur les réseaux, ces posts se trouvent promus par des algorithmes programmés pour mettre en avant les contenus capables d’attirer l’attention et de déclencher des réponses, dont les messages clivants font partie.

À contrario, la majorité des utilisateurs, plus modérée et moins péremptoire, est réticente à se lancer dans des discussions politiques qui récompensent rarement la bonne foi argumentative et qui dégénèrent souvent en « shitstorms » (c.-à-d., en déchaînements de haine).

Ces biais de sélection et de perception produisent l’impression trompeuse que les convictions radicales et hostiles sont à la fois plus répandues et tolérées moralement qu’elles ne le sont en réalité.

Quand l’exposition à la différence énerve

Ceci étant dit, l’usage des réseaux sociaux semble pouvoir contribuer à augmenter l’hostilité et la radicalité politiques selon un mécanisme au moins : celui de l’exposition à des versions caricaturales et agressives des positions politiques adverses, qui agacent.

Contrairement à une croyance répandue, la plupart de nos connexions virtuelles ne prennent typiquement pas vraiment la forme de « chambres d’écho », nous isolant dans des sas d’idées politiques totalement homogènes.

Bien que certains réseaux soient effectivement construits de cette manière (4Chan ou certains sub-Reddits), les plus larges plates-formes que sont Facebook (3 milliards d’utilisateurs) et X (550 millions) nous font typiquement défiler une certaine diversité d’opinions devant les yeux. Celle-ci est en tous cas fréquemment supérieure à celle de nos relations amicales : êtes-vous encore régulièrement en contact avec des copains de collège qui ont « viré Front national » ? Probablement pas, mais il est plus probable que vous lisiez leurs posts Facebook.

Cette exposition à l’altérité idéologique est désirable, en théorie, puisqu’elle devrait permettre de nous faire découvrir les angles morts de nos connaissances et convictions politiques, notre commune humanité, et donc nous rendre à la fois plus humbles et plus respectueux les uns des autres. Malheureusement, le mode sur lequel la plupart des gens expriment leurs convictions politiques – sur les réseaux comme à la machine à café – est assez dépourvu de nuance et de pédagogie. Il tend à réduire les positions adverses à des caricatures diabolisées, et cherche moins à persuader le camp d’en face qu’à galvaniser les personnes qui sont déjà d’accord avec soi, ou à se faire bien voir d’amis politiques.

Prenant appui sur des études expérimentales déployées sur Twitter et des interviews de militants démocrates et républicains menées avec son équipe, le sociologue Chris Bail nous avertit dans son livre Le prisme des réseaux sociaux. D’après lui, une exposition répétée à des contenus peu convaincants et moqueurs produits par nos ennemis politiques peut paradoxalement renforcer les partisans dans leurs positions et identités préexistantes, plutôt que de les rapprocher intellectuellement et émotionnellement les uns des autres.

Cependant, cette relation entre usage des réseaux sociaux et polarisation politique pourrait dépendre beaucoup du temps d’exposition et n’apparaît pas dans tous les échantillons étudiés. Ainsi, des études explorant les effets d’un arrêt de l’utilisation de Facebook et d’Instagram n’observent pas que l’utilisation de ces médias sociaux polarise de façon détectable les opinions politiques des utilisateurs.

Rappelons-nous toujours que les discours pointant des menaces pesant sur la société jouissent d’un avantage concurrentiel considérable sur le marché des idées et des conversations, en raison de leur attractivité pour nos esprits. Il convient donc d’approcher la question des liens entre réseaux sociaux, hostilité et polarisation politique avec nuance, en évitant les travers symétriques de l’optimisme béat et de la panique collective.

DensePose From WiFi

Jiaqi Geng, Dong Huang, Fernando De la Torre 31 Dec 2022

Abstract

Advances in computer vision and machine learning techniques have

led to significant development in 2D and 3D human pose estimation

from RGB cameras, LiDAR, and radars. However, human pose esti-

mation from images is adversely affected by occlusion and lighting,

which are common in many scenarios of interest. Radar and LiDAR

technologies, on the other hand, need specialized hardware that is

expensive and power-intensive. Furthermore, placing these sensors

in non-public areas raises significant privacy concerns.

To address these limitations, recent research has explored the use

of WiFi antennas (1D sensors) for body segmentation and key-point

body detection. This paper further expands on the use of the WiFi

signal in combination with deep learning architectures, commonly

used in computer vision, to estimate dense human pose correspon-

dence. We developed a deep neural network that maps the phase

and amplitude of WiFi signals to UV coordinates within 24 human

regions. The results of the study reveal that our model can estimate

the dense pose of multiple subjects, with comparable performance

to image-based approaches, by utilizing WiFi signals as the only

input. This paves the way for low-cost, broadly accessible, and

privacy-preserving algorithms for human sensing.

Densepose

Here lies the internet, murdered by generative AI

Corruption everywhere, even in YouTube's kids content

Erik Hoel Feb 27, 2024

Art for The Intrinsic Perspective is by Alexander Naughton

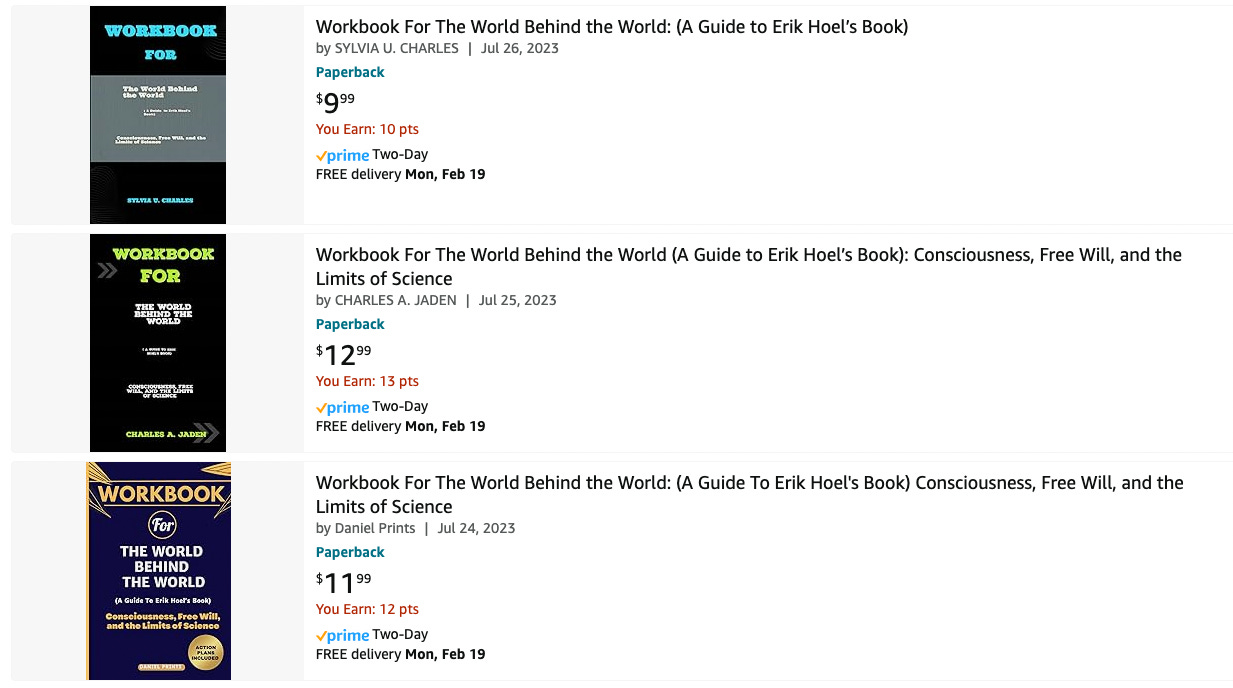

The amount of AI-generated content is beginning to overwhelm the internet. Or maybe a better term is pollute. Pollute its searches, its pages, its feeds, everywhere you look. I’ve been predicting that generative AI would have pernicious effects on our culture since 2019, but now everyone can feel it. Back then I called it the coming “semantic apocalypse.” Well, the semantic apocalypse is here, and you’re being affected by it, even if you don’t know it. A minor personal example: last year I published a nonfiction book, The World Behind the World, and now on Amazon I find this.

What, exactly, are these “workbooks” for my book? AI pollution. Synthetic trash heaps floating in the online ocean. The authors aren’t real people, some asshole just fed the manuscript into an AI and didn’t check when it spit out nonsensical summaries. But it doesn’t matter, does it? A poor sod will click on the $9.99 purchase one day, and that’s all that’s needed for this scam to be profitable since the process is now entirely automatable and costs only a few cents. Pretty much all published authors are affected by similar scams, or will be soon.

Now that generative AI has dropped the cost of producing bullshit to near zero, we see clearly the future of the internet: a garbage dump. Google search? They often lead with fake AI-generated images amid the real things. Post on Twitter? Get replies from bots selling porn. But that’s just the obvious stuff. Look closely at the replies to any trending tweet and you’ll find dozens of AI-written summaries in response, cheery Wikipedia-style repeats of the original post, all just to farm engagement. AI models on Instagram accumulate hundreds of thousands of subscribers and people openly shill their services for creating them. AI musicians fill up YouTube and Spotify. Scientific papers are being AI-generated. AI images mix into historical research. This isn’t mentioning the personal impact too: from now on, every single woman who is a public figure will have to deal with the fact that deepfake porn of her is likely to be made. That’s insane.

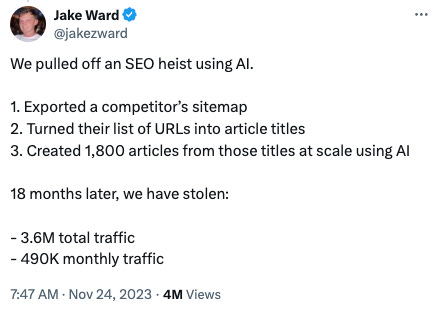

And rather than this being pure skullduggery, people and institutions are willing to embrace low-quality AI-generated content, trying to shift the Overton window to make things like this acceptable:

That’s not hardball capitalism. That’s polluting our culture for your own minor profit. It’s not morally legitimate for the exact same reasons that polluting a river for a competitive edge is not legitimate. Yet name-brand media outlets are embracing generative AI just like SEO-spammers are, for the same reasons.

E.g., investigative work at Futurism caught Sports Illustrated red-handed using AI-generated articles written by fake writers. Meet Drew Ortiz.

He doesn’t exist. That face is an AI-generated portrait, which was previously listed for sale on a website. As Futurism describes:

Ortiz isn't the only AI-generated author published by Sports Illustrated, according to a person involved with the creation of the content…

"At the bottom [of the page] there would be a photo of a person and some fake description of them like, 'oh, John lives in Houston, Texas. He loves yard games and hanging out with his dog, Sam.' Stuff like that," they continued. "It's just crazy."

This isn’t what everyone feared, which is AI replacing humans by being better—it’s replacing them because AI is so much cheaper. Sports Illustrated was not producing human-quality level content with these methods, but it was still profitable.

The AI authors' writing often sounds like it was written by an alien; one Ortiz article, for instance, warns that volleyball "can be a little tricky to get into, especially without an actual ball to practice with."

Sports Illustrated, in a classy move, deleted all the evidence. Drew was replace by Sora Tanaka, bearing a face also listed for sale on the same website with the description of a “joyful asian young-adult female with long brown hair and brown eyes.”

Given that even prestigious outlets like The Guardian refuse to put any clear limits on their use of AI, if you notice odd turns of phrase or low-quality articles, the likelihood that they’re written by an AI, or with AI-assistance, is now high.

Sadly, the people affected the most by generative AI are the ones who can’t defend themselves. Because they don’t even know what AI is. Yet we’ve abandoned them to swim in polluted information currents. I’m talking, unfortunately, about toddlers. Because let me introduce you to…

the hell that is AI-generated children’s YouTube content.

YouTube for kids is quickly becoming a stream of synthetic content. Much of it now consists of wooden digital characters interacting in short nonsensical clips without continuity or purpose. Toddlers are forced to sit and watch this runoff because no one is paying attention. And the toddlers themselves can’t discern that characters come and go and that the plots don’t make sense and that it’s all just incoherent dream-slop. The titles don’t match the actual content, and titles that are all the parents likely check, because they grew up in a culture where if a YouTube video said BABY LEARNING VIDEOS and had a million views it was likely okay. Now, some of the nonsense AI-generated videos aimed at toddlers have tens of millions of views.

Here’s a behind-the-scenes video on a single channel that made 1.2 million dollars via AI-generated “educational content” aimed at toddlers.

As the video says:

These kids, when they watch these kind of videos, they watch them over and over and over again.

They aren’t confessing. They’re bragging. And the particular channel they focus on isn’t even the worst offender—at least that channel’s content mostly matches the subheadings and titles, even if the videos are jerky, strange, off-putting, repetitious, clearly inhuman. Other channels, which are also obviously AI-generated, get worse and worse. Here’s a “kid’s education” channel that is AI-generated (took about one minute to find) with 11.7 million subscribers.

They don’t use proper English, and after quickly going through some shapes like the initial video title promises (albeit doing it in a way that makes you feel like you’re going insane) the rest of the video devolves into randomly-generated rote tasks, eerie interactions, more incorrect grammar, and uncanny musical interludes of songs that serve no purpose but to pad the time. It is the creation of an alien mind.

Here’s an example of the next frontier: completely start-to-finish AI-generated music videos for toddlers. Below is a how-to video for these new techniques. The result? Nightmarish parrots with twisted double-beaks and four mutated eyes singing artificial howls from beyond. Click and behold (or don’t, if you want to sleep tonight).

All around the nation there are toddlers plunked down in front of iPads being subjected to synthetic runoff, deprived of human contact even in the media they consume. There’s no other word but dystopian. Might not actual human-generated cultural content normally contain cognitive micro-nutrients (like cohesive plots and sentences, detailed complexity, reasons for transitions, an overall gestalt, etc) that the human mind actually needs? We’re conducting this experiment live. For the first time in history developing brains are being fed choppy low-grade and cheaply-produced synthetic data created en masse by generative AI, instead of being fed with real human culture. No one knows the effects, and no one appears to care. Especially not the companies, because…

OpenAI has happily allowed pollution.

Why blame them, specifically? Well, first of all, their massive impact—e.g., most of the kids videos are built from scripts generated by ChatGPT. And more generally, what AI capabilities are considered okay to deploy has long been a standard set by OpenAI. Despite their supposed safety focus, OpenAI failed to foresee that its creations would thoroughly pollute the internet across all platforms and services. You can see this failure in how they assessed potential negative outcomes in the announcement of GPT-2 on their blog, back in 2019. While they did warn that these models could have serious longterm consequences for the information ecosystem, the specifics they were concerned with were things like:

Generate misleading news articles

Impersonate others online

Automate the production of abusive or faked content to post on social media

Automate the production of spam/phishing content

This may sound kind of in line with what’s happened, but if you read further, it becomes clear that what they meant by “faked content” was mainly malicious actors promoting misinformation, or the same shadowy malicious actors using AI to phish for passwords, etc.

These turned out to be only minor concerns compared to AI’s cultural pollution. OpenAI kept talking about “actors” when they should have been talking about “users.” Because it turns out, all AI-generated content is fake! Or it’s all kind of fake. AI-written websites, now sprouting up like an unstoppable invasive species, don’t necessarily have an intent to mislead; it’s just that AI content is low-effort banalities generated for pennies, so you can SEO spam and do all sorts of manipulative games around search to attract eyeballs and ad revenue.

That is, the OpenAI team didn’t stop to think that regular users just generating mounds of AI-generated content on the internet would have very similar negative effects to as if there were a lot of malicious use by intentional bad actors. Because there’s no clear distinction! The fact that OpenAI was both honestly worried about negative effects, and at the same time didn’t predict the enshittification of the internet they spearheaded, should make us extremely worried they will continue to miss the negative downstream effects of their increasingly intelligent models. They failed to foresee the floating mounds of clickbait garbage, the synthetic info-trash cities, all to collect clicks and eyeballs—even from innocent children who don’t know any better. And they won’t do anything to stop it, because…

AI pollution is a tragedy of the commons.

This term, "tragedy of the commons,” originated in the rising environmentalism of the 20th century, and would lead to many of the regulations that keep our cities free of smog and our rivers clean. Garrett Hardin, an ecologist and biologist, coined it in an article in [Science](https://math.uchicago.edu/~shmuel/Modeling/Hardin, Tragedy of the Commons.pdf) in 1968. The article is still instructively relevant. Hardin wrote:

An implicit and almost universal assumption of discussions published in professional and semipopular scientific journals is that the problem under discussion has a technical solution…

He goes on to discuss several problems for which there are no technical solutions, since rational actors will drive the system toward destruction via competition:

The tragedy of the commons develops in this way. Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. Such an arrangement may work reasonably satisfactorily for centuries because tribal wars, poaching, and disease keep the numbers of both man and beast well below the carrying capacity of the land. Finally, however, comes the day of reckoning, that is, the day when the long-desired goal of social stability becomes a reality. At this point, the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy.

One central example of Hardin’s became instrumental to the environmental movement.

… the tragedy of the commons reappears in problems of pollution. Here it is not a question of taking something out of the commons, but of putting something in—sewage, or chemical, radioactive, and heat wastes into water; noxious and dangerous fumes into the air; and distracting and unpleasant advertising signs into the line of sight. The calculations of utility are much the same as before. The rational man finds that his share of the cost of the wastes he discharges into the commons is less than the cost of purifying his wastes before releasing them. Since this is true for everyone, we are locked into a system of "fouling our own nest," so long as we behave only as independent, rational, free-enterprisers.

We are currently fouling our own nests. Since the internet economy runs on eyeballs and clicks the new ability of anyone, anywhere, to easily generate infinite low-quality content via AI is now remorselessly generating tragedy.

The solution, as Hardin noted, isn’t technical. You can’t detect AI outputs reliably anyway (another initial promise that OpenAI abandoned). The companies won’t self regulate, given their massive financial incentives. We need the equivalent of a Clean Air Act: a Clean Internet Act. We can’t just sit by and let human culture end up buried.

Luckily we’re on the cusp of all that incredibly futuristic technology promised by AI. Any day now, our GDP will start to rocket forward. In fact, soon we’ll cure all disease, even aging itself, and have robot butlers and Universal Basic Income and high-definition personalized entertainment. Who cares if toddlers had to watch inhuman runoff for a few billion years of viewing-time to make the future happen? It was all worth it. Right? Let’s wait a little bit longer. If we wait just a little longer utopia will surely come.

We Need To Rewild The Internet

The internet has become an extractive and fragile monoculture. But we can revitalize it using lessons learned by ecologists.

By Maria Farrell and Robin Berjon April 16, 2024

“The word for world is forest” — Ursula K. Le Guin

In the late 18th century, officials in Prussia and Saxony began to rearrange their complex, diverse forests into straight rows of single-species trees. Forests had been sources of food, grazing, shelter, medicine, bedding and more for the people who lived in and around them, but to the early modern state, they were simply a source of timber.

So-called “scientific forestry” was that century’s growth hacking. It made timber yields easier to count, predict and harvest, and meant owners no longer relied on skilled local foresters to manage forests. They were replaced with lower-skilled laborers following basic algorithmic instructions to keep the monocrop tidy, the understory bare.

Information and decision-making power now flowed straight to the top. Decades later when the first crop was felled, vast fortunes were made, tree by standardized tree. The clear-felled forests were replanted, with hopes of extending the boom. Readers of the American political anthropologist of anarchy and order, James C. Scott, know [what happened](https://files.libcom.org/files/Seeing Like a State - James C. Scott.pdf) next.

It was a disaster so bad that a new word, Waldsterben, or “forest death,” was minted to describe the result. All the same species and age, the trees were flattened in storms, ravaged by insects and disease — even the survivors were spindly and weak. Forests were now so tidy and bare, they were all but dead. The first magnificent bounty had not been the beginning of endless riches, but a one-off harvesting of millennia of soil wealth built up by biodiversity and symbiosis. Complexity was the goose that laid golden eggs, and she had been slaughtered.

The story of German scientific forestry transmits a timeless truth: When we simplify complex systems, we destroy them, and the devastating consequences sometimes aren’t obvious until it’s too late.

That impulse to scour away the messiness that makes life resilient is what many conservation biologists call the “pathology of command and control.” Today, the same drive to centralize, control and extract has driven the internet to the same fate as the ravaged forests.

The internet’s 2010s, its boom years, may have been the first glorious harvest that exhausted a one-time bonanza of diversity. The complex web of human interactions that thrived on the internet’s initial technological diversity is now corralled into globe-spanning data-extraction engines making huge fortunes for a tiny few.

Our online spaces are not ecosystems, though tech firms love that word. They’re plantations; highly concentrated and controlled environments, closer kin to the industrial farming of the cattle feedlot or battery chicken farms that madden the creatures trapped within.

We all know this. We see it each time we reach for our phones. But what most people have missed is how this concentration reaches deep into the internet’s infrastructure — the pipes and protocols, cables and networks, search engines and browsers. These structures determine how we build and use the internet, now and in the future.

They’ve concentrated into a series of near-planetary duopolies. For example, as of April 2024, Google and Apple’s internet browsers have captured almost 85% of the world market share, Microsoft and Apple’s two desktop operating systems over 80%. Google runs 84% of global search and Microsoft 3%. Slightly more than half of all phones come from Apple and Samsung, while over 99% of mobile operating systems run on Google or Apple software. Two cloud computing providers, Amazon Web Services and Microsoft’s Azure [make up](https://www.hava.io/blog/2024-cloud-market-share-analysis-decoding-industry-leaders-and-trends#:~:text=Amazon Web Services (AWS) maintains,in the Asia-Pacific market.) over 50% of the global market. Apple and Google’s email clients manage nearly 90% of global email. Google and Cloudflare serve around 50% of global domain name system requests.

Two kinds of everything may be enough to fill a fictional ark and repopulate a ruined world, but can’t run an open, global “network of networks” where everyone has the same chance to innovate and compete. No wonder internet engineer Leslie Daigle termed the concentration and consolidation of the internet’s technical architecture “‘climate change’ of the Internet ecosystem.”

Walled Gardens Have Deep Roots

The internet made the tech giants possible. Their services have scaled globally, via its open, interoperable core. But for the past decade, they’ve also worked to enclose the varied, competing and often open-source or collectively provided services the internet is built on into their proprietary domains. Although this improves their operational efficiency, it also ensures that the flourishing conditions of their own emergence aren’t repeated by potential competitors. For tech giants, the long period of open internet evolution is over. Their internet is not an ecosystem. It’s a zoo.

Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta are consolidating their control deep into the underlying infrastructure through acquisitions, vertical integration, building proprietary networks, creating chokepoints and concentrating functions from different technical layers into a single silo of top-down control. They can afford to, using the vast wealth reaped in their one-off harvest of collective, global wealth.

“That impulse to scour away the messiness that makes life resilient is what many conservation biologists call the ‘pathology of command and control.’”

Taken together, the enclosure of infrastructure and imposition of technology monoculture forecloses our futures. Internet people like to talk about “the stack,” or the layered architecture of protocols, software and hardware, operated by different service providers that collectively delivers the daily miracle of connection. It’s a complicated, dynamic system with a basic value baked into the core design: Key functions are kept separate to ensure resilience, generality and create room for innovation.

Initially funded by the U.S. military and designed by academic researchers to function in wartime, the internet evolved to work anywhere, in any condition, operated by anyone who wanted to connect. But what was a dynamic, ever-evolving game of Tetris with distinct “players” and “layers” is today hardening into a continent-spanning system of compacted tectonic plates. Infrastructure is not just what we see on the surface; it’s the forces below, that make mountains and power tsunamis. Whoever controls infrastructure determines the future. If you doubt that, consider that in Europe we’re still using roads and living in towns and cities the Roman Empire mapped out 2,000 years ago.

In 2019, some internet engineers in the global standards-setting body, the Internet Engineering Task Force, raised the alarm. Daigle, a respected engineer who had previously chaired its oversight committee and internet architecture board, wrote in a policy brief that consolidation meant network structures were ossifying throughout the stack, making incumbents harder to dislodge and violating a core principle of the internet: that it does not create “permanent favorites.” Consolidation doesn’t just squeeze out competition. It narrows the kinds of relationships possible between operators of different services.

As Daigle put it: “The more proprietary solutions are built and deployed instead of collaborative open standards-based ones, the less the internet survives as a platform for future innovation.” Consolidation kills collaboration between service providers through the stack by rearranging an array of different relationships — competitive, collaborative — into a single predatory one.

Since then, standards development organizations started several initiatives to name and tackle infrastructure consolidation, but these floundered. Bogged down in technical minutiae, unable to separate themselves from their employers’ interests and deeply held professional values of simplification and control, most internet engineers simply couldn’t see the forest for the trees.

Up close, internet concentration seems too intricate to untangle; from far away, it seems too difficult to deal with. But what if we thought of the internet not as a doomsday “hyperobject,” but as a damaged and struggling ecosystem facing destruction? What if we looked at it not with helpless horror at the eldritch encroachment of its current controllers, but with compassion, constructiveness and hope?

Technologists are great at incremental fixes, but to regenerate entire habitats, we need to learn from ecologists who take a whole-systems view. Ecologists also know how to keep going when others first ignore you and then say it’s too late, how to mobilize and work collectively, and how to build pockets of diversity and resilience that will outlast them, creating possibilities for an abundant future they can imagine but never control. We don’t need to repair the internet’s infrastructure. We need to rewild it.

What Is Rewilding?

Rewilding “aims to restore healthy ecosystems by creating wild, biodiverse spaces,” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. More ambitious and risk-tolerant than traditional conservation, it targets entire ecosystems to make space for complex food webs and the emergence of unexpected interspecies relations. It’s less interested in saving specific endangered species. Individual species are just ecosystem components, and focusing on components loses sight of the whole. Ecosystems flourish through multiple points of contact between their many elements, just like computer networks. And like in computer networks, ecosystem interactions are multifaceted and generative.

Rewilding has much to offer people who care about the internet. As Paul Jepson and Cain Blythe wrote in their book “Rewilding: The Radical New Science of Ecological Recovery,” rewilding pays attention “to the emergent properties of interactions between ‘things’ in ecosystems … a move from linear to systems thinking.”

It’s a fundamentally cheerful and workmanlike approach to what can seem insoluble. It doesn’t micromanage. It creates room for “ecological processes [that] foster complex and self-organizing ecosystems.” Rewilding puts into practice what every good manager knows: Hire the best people you can, provide what they need to thrive, then get out of the way. It’s the opposite of command and control.

“The complex web of human interactions that thrived on the internet’s initial technological diversity is now corralled into globe-spanning data-extraction engines making huge fortunes for a tiny few.”

Rewilding the internet is more than a metaphor. It’s a framework and plan. It gives us fresh eyes for the wicked problem of extraction and control, and new means and allies to fix it. It recognizes that ending internet monopolies isn’t just an intellectual problem. It’s an emotional one. It answers questions like: How do we keep going when the monopolies have more money and power? How do we act collectively when they suborn our community spaces, funding and networks? And how do we communicate to our allies what fixing it will look and feel like?

Rewilding is a positive vision for the networks we want to live inside, and a shared story for how we get there. It grafts a new tree onto technology’s tired old stock.

What Ecology Knows

Ecology knows plenty about complex systems that technologists can benefit from. First, it knows that shifting baselines are real.

If you were born around the 1970s, you probably remember many more dead insects on the windscreen of your parents’ car than on your own. Global land-dwelling insect populations are dropping about 9% a decade. If you’re a geek, you probably programmed your own computer to make basic games. You certainly remember a web with more to read than the same five websites. You may have even written your own blog.

But many people born after 2000 probably think a world with few insects, little ambient noise from birdcalls, where you regularly use only a few social media and messaging apps (rather than a whole web) is normal. As Jepson and Blythe wrote, shifting baselines are “where each generation assumes the nature they experienced in their youth to be normal and unwittingly accepts the declines and damage of the generations before.” Damage is already baked in. It even seems natural.